Here’s your permission to go ahead and break things

Finding your appetite for destruction

As I talked about in my last blog post, design critique should be a way that teams create a culture of healthy feedback. I explained that we critique things by trying to break them together:

Sometimes you have to break things or pull them apart to make them work better. Simpler, clearer, faster.

Breaking things is about finding different ways to put the pieces back together. It’s understanding how things work, what is essential, and what can be taken away. It’s questioning our assumptions about how something is constructed or engineered in order to reinvent it.

In summary, designers need to pull things apart. It’s the process of breaking things, or learning how things break, to move our thinking forward.

Creative destruction

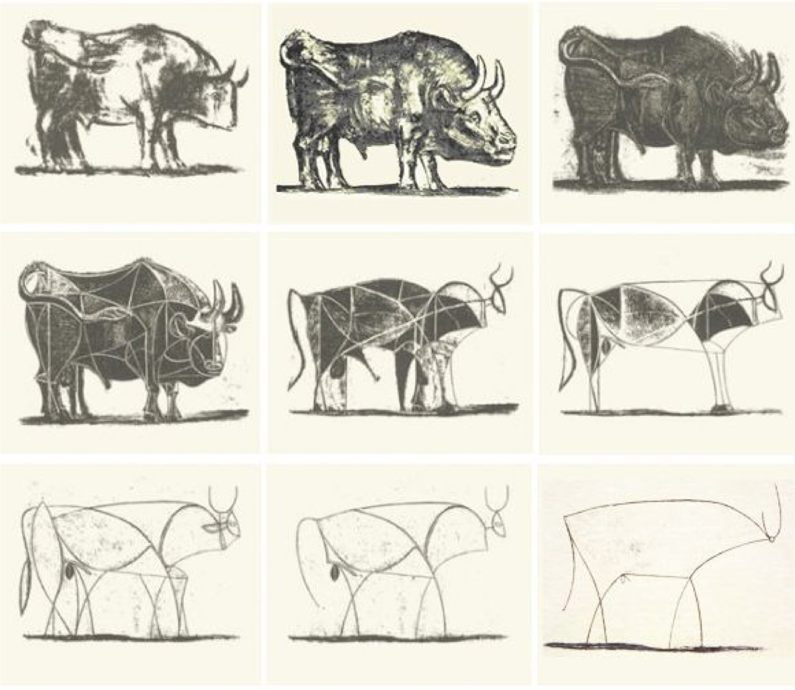

The artist Picasso described the process of simplifying his drawings and paintings as a process of ‘destruction’. To him, making something simple was about a process of reduction until he was left with what he described as the essential essential truth or the essence of a thing.

In the book Think like an Artist, Will Gompertz describes how Apple apparently used this series of Picasso drawings as part of their induction for new designers.

In this composition ‘The Bull’, Picasso shows a series of 9 images. It’s unusual because he wasn’t known for showing his process.

In each sketch Picasso simplifies the image further, gradually breaking down the composition. As the book explains: “…[Picasso is] showing us that creativity isn’t about making additions; it is about making subtractions. Ideas need honing, simplifying and focussing”.

The art of creative destruction, or breaking things down like this, is very powerful. It’s about being prepared to keep refining and simplifying something.

Taking things apart

Most people have a story of somebody, usually a child, taking something apart to see how it works.

In our family, my wife’s grandfather (now aged 101) famously took apart the engine of his parents car when he was just 11 years old. He quickly realised he was going to need a little more help to put it back together again.

The point is that we learn about how things work by breaking them down or deconstructing them.

We pull things apart to understand why they work, even when putting them back together can be hard.

Sometimes this gets messy, but there’s always room for improvement. Breaking things into smaller parts or deconstructing them is an important part of the process.

Big breaks

The problem with re-inventing things is that we risk breaking how things work right now.

We break the present, to create the future.

When I worked for FreeAgent–an online accountancy product–I was very aware that the product we were developing was breaking things. In this example, FreeAgent was changing the traditional relationships between freelancers and accountancy firms. It was breaking the accepted working model–democratising accounting.

The potential of digital and the internet was good for FreeAgent customers, but not so good for the traditional accountancy firms not ready to embrace the change.

In contrast, those accountants that have embraced the potential of digital may have experienced the things around them breaking, but they’ve also been adaptable to the changes. Many have benefited.

Eventually, what breaks catches up with us. We need to be ready to adapt to the changes driven by digital and the potential of a more connected society.

Partial steps

Sometimes breaking things is how we change the perception of a ‘standard’ or redefine what’s ‘normal’.

In recent talks I’ve been using the example of this years’ iPhone 7.

Apple removed the headphone socket, a standard in phones, and music players for decades. This generated much media comment, but it’s all part of Apple’s process of moving their products forward. It was never going to be a popular decision but it’s allowed them to shift their focus onto other things, or making the iPhone better in different ways. For example, making room for a better better camera.

Innovation, if you can call bluetooth headphones innovation, is about breaking an existing cycle of behaviour, dependency, or changing customer expectations.

Yesterday’s controversial removal of the CD-ROM drive in Apple laptops is today’s headphone jack discussions on social media.

Things should break well

Breaking things should mean that they don’t remain broken. In fact, part of the process is asking “how well does this break?”

As with the Apple example, we soon find out how well people adapt when there’s a forced change to an activity as familiar as putting on a pair of headphones.

There’s a famous quote: “An escalator can never break, it can only become stairs”. Still functional, it remains accessible.

There’s a responsibility that comes with the power of breaking things. Deconstruction is a skill and all design has ethical implications whether we choose to think about them or not.

As a rule of thumb, breaking things should not exclude anyone. We should be thinking about progressive enhancement or simply how well things break.

People shouldn’t always have to be aware of how things are breaking around them. Good design should help us seamlessly adapt as things begin to break.

Don’t be afraid to break things

So here’s your permission. Find your appetite for creative destruction.

Sometimes design needs to start with heavy hand. It’s prepared to break things to move forward, and it’s then prepared to work through the break points.

Go ahead and break things.

This blog post is part of an experiment where I’m writing and publishing something everyday. This is day 7: everyday is an opportunity to write something – previous blog posts.

This is my blog where I’ve been writing for 18 years. You can follow all of my posts by subscribing to this RSS feed. You can also find me on Bluesky, less frequently now on X (formally Twitter), and on LinkedIn.